In Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop Jeff Chang declared, “fevered dreams of progress had brought fires to the Bronx and Kingston. The hip-hop generation, it might be said, was born in these fires.” This resonates on multiple levels, in that his statement elicits historically relevant events, to the South Bronx, and consequently suggests a socially critical aspect to hip-hop culture. This concentration on the socio-political implications of the rapid urbanization and class polarization in the United States of America, New York City specifically, in reference to the growth of hip-hop culture, positions its derivative art forms (music, dance, graffiti, etc.) as socio-politically relevant. In this way, revolutionarily ground breaking, hip-hop songs, such as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s, The Message, and Public Enemy’s, 911 is a Joke, can be viewed dually as artistic cultural narratives, and socio-political responses to innately oppressive environments.

Jeff Chang’s concentration on the urban politics and planning of the urbanization of the New York suburbs is evident immediately through both his explicit and implicit allusions to the socio-political issues found in the South Bronx. Chang explicitly refers to Robert Moses’ Cross-Bronx Expressway and its consequent effects on the community when he writes: “By the end of the decade (1960s), half of the whites were gone from the South Bronx. They moved north to the wide-open spaces of Westchester County or the northern reaches of Bronx County. They followed Moses’ Cross-Bronx and Bruckner Expressways to the promise of ownership in one of the 15,000 new apartments in Moses’ Co-Op City.”

The effects of the industrialized urban planning system under Robert Moses, is later juxtaposed with a more covert observation of the ultimate social effects of urban planning through Chang’s connection to the birth of hip-hop culture when he asserts: “fevered dreams of progress had brought fires to the Bronx and Kingston. The hip-hop generation, it might be said, was born in these fires” . Such arsenic riddled diction, including “fevered dreams,” and “fire,” reads as a direct reference to the widespread “arson as a form of insurance policy” in the region. Chang notes earlier in Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, that “between 1973 and 1977, 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx alone” (13), speaking directly to his later illicit reference to such infrastructure issues. Furthermore, Chang’s diction, “the hip-hop generation, it might be said, was born in these fires,”, not only suggests that the socio-political events that led to the arson issues in the South Bronx region, in turn gave birth to hip-hop; in other words, suggesting that hip-hop can viewed as a vehicle to respond to social injustice. Hip-hop gave a voice to the population who suffered from the results of urban renewal gone wrong.

In this way, both Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s, The Message, and Public Enemy’s, 911 is a Joke, read both as cultural narratives and criticisms, as they satirically speak to mainstream ideals regarding inner cities, and hip-hop culture. Chang writes, “But some argued that the South Bronx presented indisputable proof that poor Black and Latinos were not interested in improving their lives.” This notion of the decision by “Blacks and Latinos” to live a stagnant, poverty stricken, lifestyle is directly referred to in The Message; it states: “got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice; I tried to get away but I couldn’t get far/ ‘Cause a man with a tow truck repossessed my car.” These lyrics speak to the Catch-22 at the root in the urban struggles of the South Bronx, a response to industrialized urban planning, in that the inner-city and its inhabitants are too poor to support each other. Causing a never ending cycle of vocational poverty, and incarceration.

Similarly, Chang writes of the public policy of “benign neglect,” writing: “When it became public, “benign neglect” became a rallying cry to justify reductions in social services to the inner cities.” The effects of benign neglect are narrated in Public Enemy’s 911 is a Joke, as the group satirically criticizes the inefficiency and racial bias of the police in New York City. 911 is a Joke declares: “911 is a joke we don’t want ‘em/ I call a cab cause a cab will come quicker.” In this way, such social awareness, dictated in hip-hop songs, and embedded in hip-hop culture, can be viewed as a commentary on the causes and effects of social injustice that the oppressed community could relate to.

The Bronx was burning, literally and figuratively and the affected community needed a way to communicate its outrage and discontent with the resultant status quo. That voice manifested itself in hip-hop, a decade later, and can still be heard as a rallying cry today, eliciting a socio-political dialogue.

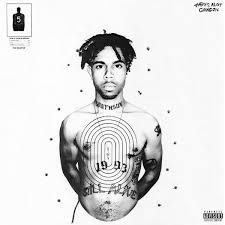

Chicago-native, Vic Mensa, has more recently turned to hip-hop in attempts to communicate social injustices in what has been described as a war torn Chicago community- Chiraq. Vic’s recent song, “16 Shots,” speaks to the Black Lives Matter movement, detailing the Laquan Macdonald’s shooting, and in doing so speaks to the socio-political landscape of the South-Side of Chicago. However Mensa’s recent song, “16 Shots,” manipulates the idea of Chiraq as the title usually carries a civil war connotation, as black on black crimes riddle the community. However Mensa spins this preconception of Chiraq, instead suggesting a more unified community, at war with the police, rather than themselves. “16 Shots” begins: “Ready for the war we got our boots strapped/ 100 deep on State Street, where the troops at?” Written as a response to Laquan Mcdonald’s death, these opening bars suggest a cause and effect relationship, as if to define the Mcdonald’s shooting as a symbolical act of war.

This sentiment of judicial discontent is reminiscent of Public Enemy’s 911 is a Joke speaking both to the socio-critical aspect of Hip-Hop, as well as a recurrent socio-political issue. In fact, Mensa’s “16 Shots,” refers to this idea that the same issues exist today as did in the 1960’ and ‘70s, declaring: “There’s a war on drugs, but the drugs keep winnin’/ There’s a war on guns, but the guns keep ringin’.” By coupling President Nixon’s failed 1971 “War on Drugs,” with President Obama’s 2013 “War on Guns,” Mensa suggests that his displeasure extends beyond the police, and requires intricate political action.

One thought on “Hip-Hop’s History of Social Criticism”

Awesome Blogpost Thanks for sharing.